Last year, I began to receive complaints from authors with UK-based Fortis Publishing.

Issues cited included poorly proofed and/or formatted books (missing images or chapters, for example); little or no marketing; delayed or missing sales reports and royalty payments; poor communication and failure to respond to emails and questions, editing fees, possible fictitious staff members, authors’ names attached without permission to book blurbs they didn’t write, and extra-contractual changes to royalty reporting schedules, despite the contract’s stipulation that modifications must be made in writing and signed by both parties.

Writers also reported substantial conflicts of interest (more on that below).

For readers of this blog, many of these complaints will seem familiar: they are among the problems most commonly faced by authors with troubled publishers. But the Fortis story is unusual, in that complaints involve not just what authors experienced after they signed their contracts, but what happened before Fortis ever offered to publish them. And both before and after have one thing in common: Fortis’s co-founder, Ken Scott.

Dive with me down the rabbit hole.

Investigating Fortis

Per Companies House, Fortis Publishing (motto: “Championing Stories That Inspire”) was incorporated in May of 2019, but doesn’t appear to have started publishing until 2020. Its current catalog of around 80 books includes original works in a variety of genres, along with a number of re-issued public domain titles. Fortis doesn’t charge publishing fees (though, as I’ve mentioned, some authors do pay for editing), but for a time it ran a pay-to-publish division, Gutenberg Press, which seems to have closed down sometime in 2024.

Fortis’s (barely) three-page, fill-in-the-blanks contract, which you can see an example of here, is woefully inadequate, lacking such important elements as an editing clause, a copyright clause, an exact schedule of royalty reporting and payment, and reversion language. Like many small presses, Fortis uses KDP to publish–not a warning sign in itself, but something that should prompt authors to consider whether the publisher offers significant benefits beyond self-publishing.

Companies House shows Fortis with one director, Kenneth James Douglas, aka Ken Scott (his pen name, and also, he told me when I contacted him for comment, the name he generally goes by). Douglas, or Scott, is one of two “persons with significant control“; the other is Fortis co-founder Reinette Visser, who remains active in that role despite resigning from Fortis in May 2024. This leaves Scott as the only permanent Fortis staff member. (Sole proprietorship is another thing authors need to carefully evaluate: one-person publishers are uniquely vulnerable to disruption, since a single family crisis or other mishap can derail the entire operation.)

Companies House provides financial filings and other documents for download (I often wish the US had an equivalent resource). Fortis’s May 31, 2024 financial statement shows £577 in assets and £530 in cash on hand (both decreases from the prior year), and £2,998 due to creditors (an increase over the prior year)–not exactly a portrait of a thriving publishing enterprise. Average number of employees over the prior year, including directors: two.

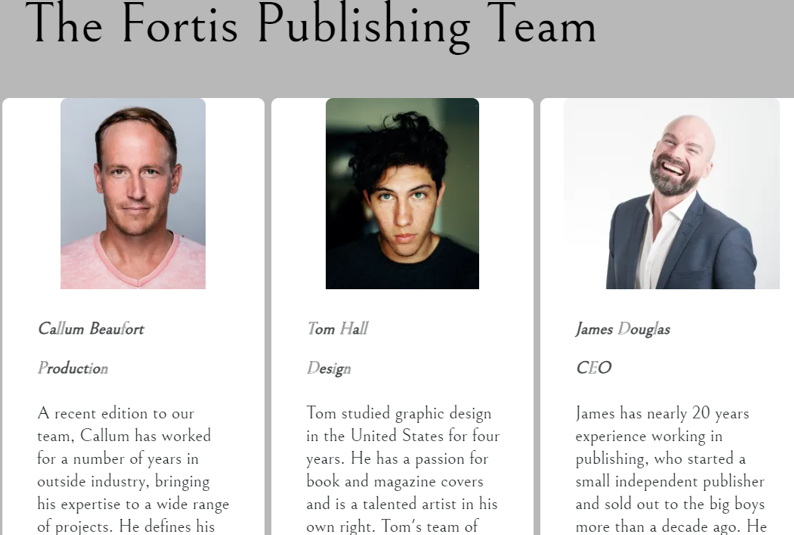

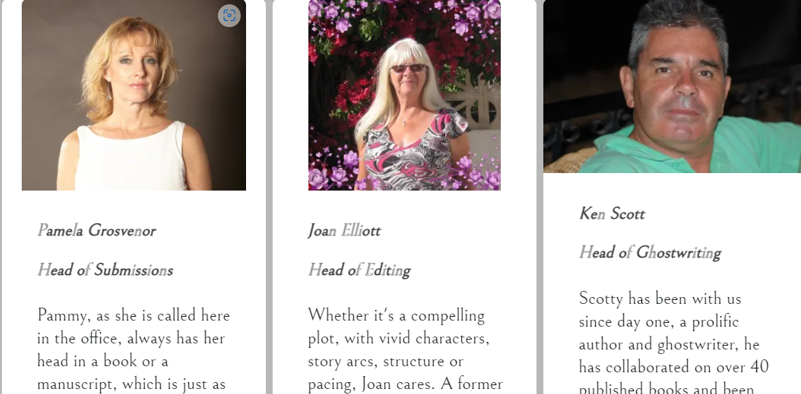

May 2024 is also when I began to receive complaints about Fortis. At the time, its website included a Meet the Team page (link, sans images, courtesy of the Wayback Machine) that showed several more than two employees.

Problem is, four of the six images above are stock photos. Here’s Callum Beaufort, aka Man-5519413, on free image site Pixabay. Pamela Grosvenor is available for free download on Pixabay. The brooding visage of Tom Hall resides on multiple stock image sites such as Unsplash, where his name is Man Wearing Black Crew-Neck Shirt. Cheery CEO James Douglas is also all over the place–Freepik, for example, where he’s known as A Man With a Beard Laughing and Wearing a Suit.

And it’s not just images. According to a person who really did work with Fortis, Beaufort, Grosvenor, et al–whose names are attached to emails and messages shared with me by authors who received them–are as imaginary as their pictures. Ditto for the positions they’re said to hold.

The two authentic images, belonging to provably real people, are of Joan Elliott, who did freelance editing for Fortis, and Scott himself (you can see the same photo on his website). Remember, though, that under his given name of Kenneth James Douglas, Scott is also the company’s Director. So actually Scott appears on the Team page twice: once as CEO under his given name (or part of it), with a fake image; and once as Head of Ghostwriting under his pen name, with a genuine image–something that certainly would encourage the average viewer to assume these were separate people.

I put all of this to Scott. He denied that that Beaufort et al were made up: they were freelancers, he said. He did admit to using false images, but claimed this was a perfectly acceptable practice to protect the identities of (real) people who didn’t want their faces shown; other businesses did the same. He didn’t acknowledge that his double inclusion, with different names and a stock image, was misleading, either. “Everything I do in the industry is under my pen name,” he told me, and gave me a list of all the famous authors who also used pen names.

Scott does nod to his given name. On contracts for his ghostwriting and agenting services, offered to authors who engaged his services prior to signing with Fortis (remember I mentioned conflicts of interest?), he’s identified as “Ken Scott aka Ken Douglas”, or “Ken Douglas aka Ken Scott”, with payment directed to the account of “K.J. Douglas”. But it’s a very sideways acknowledgment, and at least some authors who signed the contracts didn’t make the connection (as evidenced by emails shared with me that addressed both Scott and Douglas as if they were two different men). These authors, when they discovered it later, told me they absolutely did feel misled.

(“Why are you looking at this stuff in the past?” Scott asked me when I presented all of this to him. Because, I responded, a publisher’s past is directly relevant to its present.)

For whatever reason, by September 2024 Fortis had overhauled its Meet the Team page. In the new version, Beaufort, Hall, Grosvenor…and, conspicuously, James Douglas, CEO…are banished, replaced with four newcomers, two of whom are Fortis authors (according to the same Fortis insider, these individuals agreed their images could be used, but didn’t hold real positions). That would seem like some pretty major and destabilizing turnover–if, of course, the vanished staff were real.

Today, the Fortis website does not include any mention of staff at all.

The Somewhat Mysterious NSB Publishing Corp

Fortis has a relationship with another publisher, NSB Publishing Corp, which bills itself as an imprint alongside Fortis (even though there’s no parent company for them to be imprints of). NSB’s web domain was registered in September 2024 to Fortis author Nick Berg, one of the newcomers on Fortis’s September 2024 Meet the Team page. However, it appears to have had a previous life as what looks to me like a self-publishing endeavor: the only work it has ever issued is Berg’s own book, The Culture of Open, in 2016.

Scott confirmed to me that NSB is Nick Berg’s company, and told me that within twelve to eighteen months Fortis and NSB plan to merge, as part of Fortis’s expansion to the USA. When I asked why the NSB website features what appear to be fake testimonials, Scott said he wasn’t aware of that and would take it up with Berg. (Apparently he did: I spoke with Scott last week, and when I checked just now, the testimonials were gone. Thanks to the Wayback Machine, you can still see them.)

There isn’t much on the NSB website at present, and the Submit Your Manuscript button doesn’t work. But the site does includes descriptions of NSB’s publishing services, some of which are worded in a way that strongly suggests they will be pay-to-play. Scott didn’t respond to my question about this, saying only that NSB is “a work in progress” and isn’t yet active. Worth noting, though: some of the content on NSB’s website is word-for-word identical to items on Fortis’s Fortis Book Match page, where Fortis offers referrals to an un-named team of book coaches, ghostwriters, editors, and cover designers. (Fortis is on the left, NSB is on the right):

Conflicts of Interest

On his website, Ken Scott describes himself as “Author, Ghost Writer, Book Coach”. Both the website and his Reedsy listing cite multiple ghostwriting credits with a variety of publishers. He’s also a Fortis author, with several books published by the company.

For a time, Scott also operated a literary agency, The Scott Agency (now visible only via the Wayback Machine; Scott told me he closed it down eighteen months ago). Every author listed as an agency client is also a Fortis author. A number of the books he claims as ghostwriting credits also were published by Fortis. Similarly, most of the authors who contacted me wound up at Fortis because they hired Scott as their agent or their ghostwriter or their editor, and either were promised publication at the outset, or later were offered Fortis contracts. (In fact, I saw one Fortis contract that included Scott’s ghostwriting services.)

I put it to Scott that it’s a conflict of interest to steer clients who’ve engaged you to provide an unrelated service–paid or not–into your own moneymaking enterprise. He vehemently denied this, in part, he claimed, because Fortis doesn’t make any money (based on the financial statement described above, I can believe it, but that doesn’t really answer the conflict concerns). Similar tight margins, he said, explain why many authors paid for editing: Fortis, he explained, is one of the little guys, without the resources of the big behemoths like Macmillan, and just doesn’t have the capacity to provide such services free of charge.

Several of the authors who engaged Scott’s ghostwriting services told me they were unhappy with the results, feeling that their stories had been distorted or changed in negative ways. Authors who became agency clients said that as far as they knew, Scott never submitted their manuscripts to any publisher other than Fortis. When I asked about this, Scott responded with bluster, referencing his many ghostwriting credits (some of which, he said, he’d done for free) and theorizing that “two or three” authors just wanted to “blow Fortis up” and he had a good idea who they were (I pointed out that he actually had no idea who’d contacted me or what they’d told me).

The content similarities between NSB and Fortis that I’ve highlighted above also suggest the potential for conflict of interest. Might NSB be where the Fortis Book Match referral service will send authors looking for publishing services? MIght authors be shuttled between the two imprints?

The Need for Firewalls

Publishers respond in a variety of ways when I reach out to them about author complaints (that is, when they don’t just ignore me). Some spin. Some lie. Some threaten. Some engage honestly with my questions.

One of the most frequent responses is a claim of altruism. They’re just trying to help authors achieve their vision, or to amplify underrepresented voices, or to bring important stories to light, or to open doors that bigger publishers slam closed. Look at all the good books they’ve published. Look at all the authors who are happy with their experience. Those things, they feel, should more than offset whatever systemic problems or actual malfeasance is being alleged by a tiny minority of ungrateful troublemakers.

(And indeed, sometimes this can be true. Any author, with any publisher, can have a bad experience, and that experience may not reflect on the publisher as a whole. That’s why I only write articles like this when I’ve received multiple complaints, with multiple similar elements. One bad experience can be a glitch. Eight, or ten, or fifteen suggest a pattern.)

In our conversation, Scott leaned hard into the altruism defense, claiming that most Fortis authors were happy and describing how Fortis, and his own ghostwriting business, have made it possible for abuse survivors to tell their stories to the world. Fortis, he told me, is even planning to become a non-profit, which appears to be a reference to a statement on the website homepage that Fortis is “transitioning into a Community Interest Company”. (Based on this overview, I have a hard time seeing how any generalist publisher would qualify, but who knows).

I don’t see any reason to disbelieve that Scott is sincerely convinced that he and Fortis are helping writers. But the conflicts of interest and the consistency of authors’ complaints–not to mention the past deceptions and misdirections on the Fortis website, which indeed are past history but nevertheless raise troubling questions about Fortis’s relationship to the truth, point to a rather different reality.

Once upon a time, if a literary agent was also a publisher, or a ghostwriter was also an agent, it was an infallible sign of a scam. Those distinctions have blurred over the past couple of decades; plenty of reputable agents now offer paid services of various kinds, for example. But though the industry has changed, the potential conflicts of interest remain the same, and ethical practice demands some sort of firewall between publishing, agenting, and adjunct services, where provided by the same person or organization. More than anything else, the Fortis story demonstrates the need for those bright lines, and the damage that can result where they don’t exist.

Different opinion

I know several of Fortis authors and have experience with the company as a client. We have no complaints and they did a good job, paid on time and provided good services. Of course, it’s a small independent publisher so not all the resources of a larger.

It seems that complaints like this often come from rejected authors who’s work did not fit such a small publisher.

Don’t feel like a lone wolf. I have hired and fired three publishers for not doing their work. I paid one in Walnut Creek, California, one Tampa, Florida and the other one in New Jersey, who tried to use my credit card without permission. Who do you trust? Many publishers say they are in some state but actually they’re in a foreign country, like India. They are SCAMMERS! Watch and check their reviews.

Have you had any complaints about Able Publishing Press and their Authors Book Launch & Expo, Melbourne? I’m feeling very conflicted by their awards (my memoir has been nominated). On a positive note, they listed the names of judges on Instagram and Facebook and I was interviewed by a panel. But the costs and glitziness of launch and awards night are off-putting. And the fact that some of the books they publish are nominated for the awards!? I have two author friends who are going, but they don’t have the same reservations as me.

This story sounded eerily familiar. If you go the Absolute Write bewares forum and search for Kenn Scott and Kenn Douglas, you’ll find a long thread on Libros (or Wild Cherry) (https://absolutewrite.com/forums/index.php?threads/libros-international-wild-cherry-press.67865/), which sounds extremely similar to the above. Is this the same guy?

Oh. My. God. I need to do some more digging into that very long thread, but based on what I see there and also on Libros’s website (via the Wayback Machine), it looks like you’re right: this is the same Ken Scott. I even remember that thread, which happened when I was still modding at AW, but didn’t recall the Ken connection. Good catch!

Thank you. If this was not evil, perhaps it would be vastly amusing— a “publisher, ghost writer, editor, agent, philanthropist” with completely different names and radically different faces assuring you (V.S.) that he is legitimate. (But then, the USA has an entire political party like this.)

As for KDP. the terms of services have changed regarding Third Parties, and this has caused some issues when I have helped (for free) people self-publish. One is no longer allowed to let a third party use one’s KDP account to perform self-publishing and catalog maintenance. There are many (many, many, many) people on Fiverr, Upwork, and other web sites that sell KDP services using writers’ accounts— which is no longer allowed (yet they still do this).

Some people object to having publishers (not self-publishers) use KDP, yet this is not always a scam “red flag.” I publish top-tier anthologies (by autistic writers about autism, fiction and creative non-fiction) via KDP under my publishing account and business name, and I pay the authors advances on future sales; royalties if the anthology earns out; and complete rights reversals after 11 months of the release date. I do this at a financial loss: ironically, perhaps, that I really do work to amplify “marginalized voices” when scams and scammers claim “altruism.”

My point being that KDP is a valid and useful tool for small publishers as well as self-publishers.

“Speaking” of ghost-writers, as yet I have not found any ghost writers on line / Internet who are legitimate except for the hyper rare and established few. Some times on Reddit writers forums I see people who have paid for ghost-writing services, and none have been happy with the results. They did not understand the extensive time and effort it takes to work with a legitimate ghost writer— the daily discussions and feed back that can take six to nine months to get style and voice established.

Hello, I’m a first time author I’m Australian and I have or just about to publish my book. They are asking me to set up a US account a swift code tax code etc… but I am not in the US. I’m in Australia. I’m wasn’t told this information from the beginning. Am I being scammed?

My guess is that this is indeed a scam, but I need to know more. Email me in confidence: beware@sfwa.org

Your watchdog services are very much appreciated. Thank you for the time and effort you put into it.

Thank you for this great article. INKED had a disastrous ending too. Who can we trust these days? Margaret, Australia

Past is prologue: patterns of unethical behavior predict more of the same.

I feel that people who bluster and whine about their patterns of behavior being examined know very well they’re behaving unethically, whatever they tell themselves and others.

Thank you for informing us about this. It really is challenging to find a reputable agent/publisher. Once you have been scammed, it’s scary who to trust.

“It really is challenging to find a reputable agent/publisher.”

Alas, it has “always” been a challenge to find representation for a manuscript. My literary agent, whom I am infinitely pleased with, was found via MANUSCRIPT WISH LIST.

What I picked up from your exposé was that some scammers use KDP for publishing. It is my understanding that KDP does not charge anything for publishing, hence it would also be tempting for capable authors to use them directly. But I now wonder whether KDP realizes it is – perhaps inadvertently – part of the scamming industry. Would it be worthwhile your interviewing KDP to see what their position is in this regard?

Every active scammer on my Overseas Scams list uses KDP and/or IngramSpark to publish. Ditto for the many ghostwriting scams that are defrauding writers. I don’t think this is an issue that anyone at either company thinks too hard about.

I’m stealing his web banner and printing it on red t-shirts. It’s a good design. Put it on a bright non-fading red poly cotton blend with moisture wicking ….

Come and get me, Ken!

Oh, wait. He probably stole it from someone …

Can you say crook?

Thanks for this very important and extremely helpful post.

Thank you as always, Victoria Strauss, for shining a light into the dark corners of what has become our publishing world. I feel that so many of these people calling themselves publishers, editors, publicists, ghost writers are preying on peoples’ desperate desire to publish their writing and make their mark in this increasingly noisy world.

The clearest sign of shenanigans? Four white male agents at one firm? A unicorn chomping on four leaf clovers is more common.