The clauses I’m going to discuss in this post come from the contract of Shadow Light Press, a publisher of fantasy and science fiction with deep ties to the LitRPG community. The contract stirred controversy this week when it was publicly posted on Reddit–largely from people aghast at its author-unfriendliness, but also because of alleged issues around the publisher’s relationship with a major progression fantasy and LitRPG Discord server.

I’m not going to go into those issues here (you can find out more, if you like, from the comments on the Reddit post). My focus will be on the contract itself (which I can confirm is authentic: I’ve seen several other copies). My intent–as always with my posts about publishing contracts–isn’t just to call out a publisher for problematic language, but to explain why it’s problematic, with the goal of empowering my readers to better evaluate the contracts they may be offered. New writers, who may be less knowledgeable or dazzled by the prospect of publication, are especially vulnerable to predatory contracts like this one.

Oh, and I’m not a lawyer. So what follows isn’t legal commentary or advice.

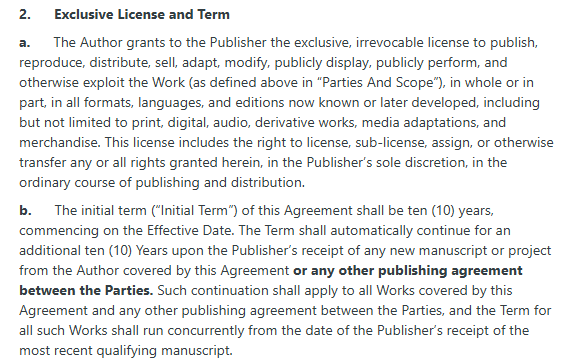

An irrevocable 10-year grant of rights that demands every right in existence and renews to infinity

In my opinion, a 10-year grant term is too long–especially for a contract that, like this one, does not include language allowing the author to revert rights once sales decline (which can happen a lot sooner than ten years). Five or seven years is preferable.

The extremely sweeping grant of rights–basically, the publisher is claiming the power to do everything and anything with every right that exists–is also a big “yikes”. A publisher, especially a small publisher, shouldn’t claim rights it hasn’t proven it’s capable of exploiting. How many foreign editions, for example, has this publisher managed to license? Additionally, a grant of rights shouldn’t be “irrevocable”: there should be provision for the author to revert rights during the contract term, even if only for breach by the publisher. (In fact, there is such a provision in the contract, so “irrevocable” shouldn’t even appear in this clause.)

Ten years, sweeping grants…these things are greedy, but they aren’t unique. Plenty of publishers make similar demands. What’s unusual here is the fact that the grant term, potentially, is a whole lot longer than ten years. Why? Because it keeps rolling over. Every time the author delivers a new series installment (the contract includes a series commitment clause binding the author to an agreed-upon number of books), another ten years gets added on. I mean, what?? If your series is a trilogy, you’re looking at a thirty-year contract? And that’s not all: you get the add-on even if the work you’re turning in is covered by a different publishing agreement. If I’m reading this right, and you have two contracts for two different series, every time you deliver an installment of either series, both contracts get an extra ten years.

It’s not often I get to say this, but I have never seen anything even similar in any other publishing contract. It’s actually hard for me to believe it’s real. I suppose it’s possible that it isn’t what the publisher intends and the wording of the clause is simply unclear. But if so, that’s just a different bad thing.

Series contracts where the author delivers installments at intervals need to be structured so that the publisher can keep all installments in print while sales are strong. But there are ways to do that fairly–for example, a life-of-copyright grant with reversion language allowing the author to revert rights to any of the books once sales drop below an agreed-upon benchmark. Or each book having its own grant term. Or even the grant of rights Shadow Light had a year ago, with a single ten-year renewal upon completion of the final installment (see the Other Concerns section, below). Unlimited rollovers are a terrible way to do it.

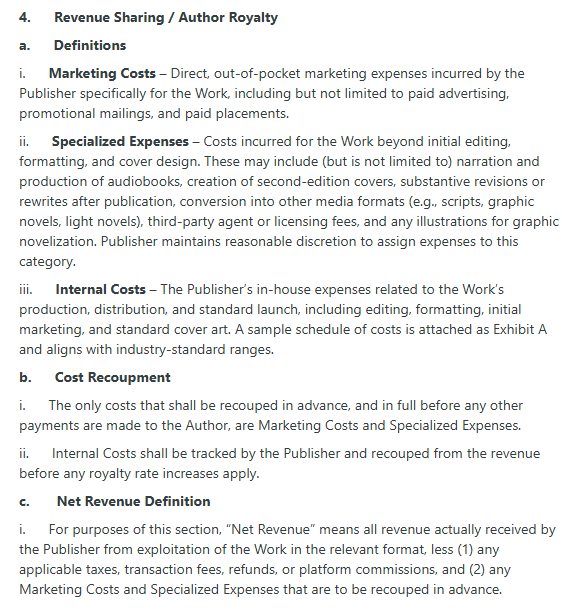

Net profit royalties and back-end vanity publishing

“Cost recoupment”, or a similar term, is not something you want to see in a publishing contract. It means that the publisher will appropriate some or all of the sales proceeds of your book in order to reimburse its production (and perhaps other) costs. This is, essentially, back-end vanity publishing. You’re not giving your publisher cash on the barrelhead, but you are agreeing that the publisher can keep money that would otherwise go to you, whether by withholding royalties or reducing royalty rates.

At Shadow Light, cost recoupment means reducing royalties, both by actual lower rates (see below) and by paying on net profit, which it misleadingly calls net revenue.

Net revenue, as generally understood, is the money the publisher actually receives from sales: list price less wholesalers’ and retailers’ discounts. Smaller publishers, especially, tend to pay royalties on net revenue rather than on list price. In this case, however, the term is defined as actual sales revenue less a menu of “marketing costs and specialized expenses”: the publisher’s net profit, in other words. Net profit royalties are the least favorable kind–not only because they reduce the amount on which your royalties are calculated, but because they can, potentially, allow a publisher to manipulate costs to make that amount is as small as possible.

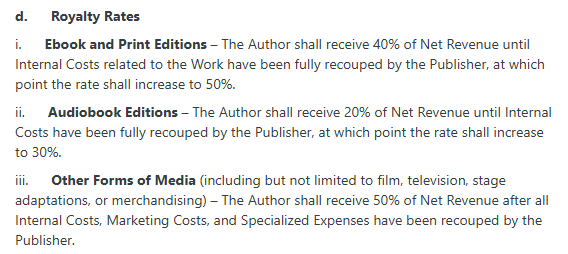

Shadow Light also recoups costs by reducing its initial royalty rate until “internal costs” have been reimbursed by sales income. From Clause 4.d.:

So the publisher pays you less while it pays itself (and remember, that reduced rate is paid on net profit, reducing it even further). Once the “internal costs” have been satisfied, you get a bump up to 50%…but it’s still a net profit royalty, so the extra 10% will probably not make a heap of difference. In fact, Clause 10, which describes the payment schedule, seems to be preparing authors to receive nothing. “These adjustments [for expenses] will be estimated by the Publisher to ensure sufficient funds are available to support the continued promotion and success of the Work…These initial royalties are often reinvested into marketing efforts to bolster the series’ success. This approach continues until sufficient funds are accumulated, allowing for the distribution of profits.”

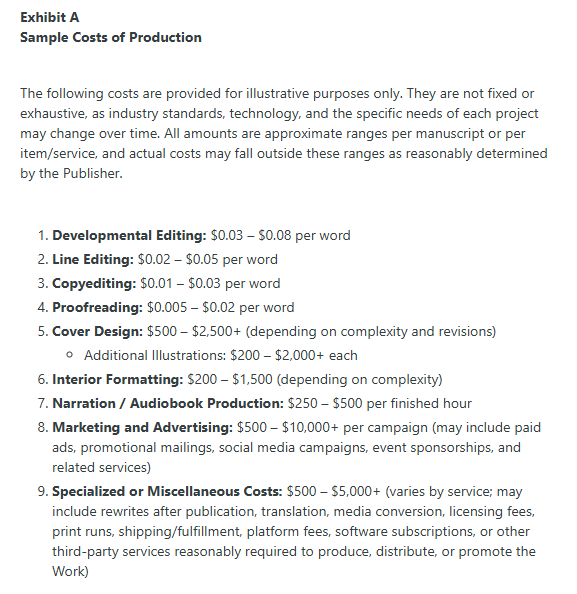

Do Shadow Light’s royalty statements break the adjustments down, so that authors have a clear picture of what expenses are being credited against their royalties? I don’t know (but they should). However, we do know what some of the expenses are likely to be, thanks to this contract addendum:

It’s notable that the upper range of costs for developmental and line editing exceed the recommended rates for professional editors suggested by the Editorial Freelancers Association. I also have a tough time crediting that a small press could actually afford to invest anything close to $10,000 in a marketing campaign.

All your world belong to us

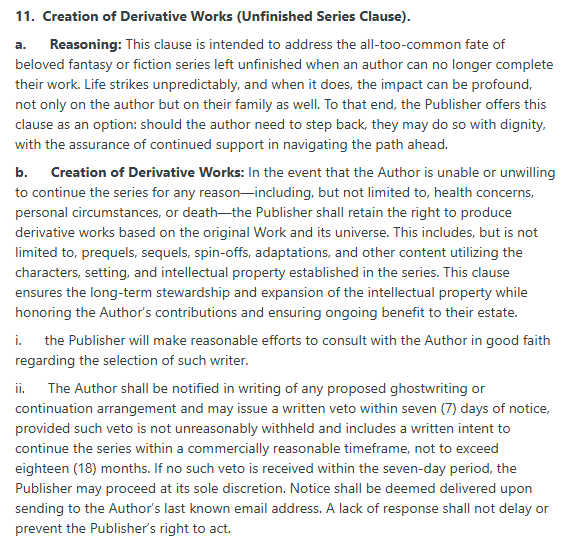

Shadow Light’s contract includes an unusual amount of verbiage explaining Why This Thing Is Good–as here, in Clause 11, which addresses what happens if the author is unable to finish a series.

The language is self-explanatory: if you can’t complete your series for any reason (other, presumably, than breach–more on that below), the publisher takes possession of it by giving itself unlimited power to produce derivative works based on it. The Why This Is Good paragraph presents this as a benefit to the author, (“step back…with dignity, with the assurance of continued support”), but in reality it’s 100% to the benefit of the publisher, who gets to continue exploiting the author’s rights, just without the author. There’s a nod to consent, with written notification and the possibility of a veto–but the veto isn’t really a veto, since it’s contingent upon the author agreeing to continue doing the thing they’d become unable to do.

This is not standard publishing contract language, and stretches the concept of derivative works to the breaking point. In fact, the sweeping terms are more like those of a work-for-hire contract, where the publisher take possession of the author’s copyright. Further to that, I find it interesting that the only mention of copyright in this contract is in the lengthy preamble and in the indemnity and warranties clauses. There’s no explicit acknowledgement of the author’s retention of copyright, or requirement that the publisher print a copyright notice in the author’s name in each edition or format of the book and require licensees to do the same (there should be).

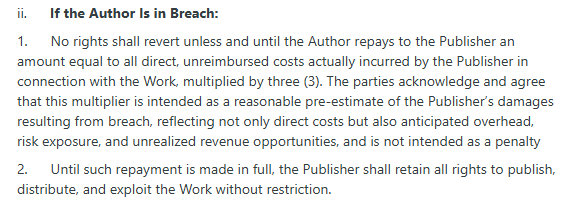

Triple damages!

If the publisher deems you to be in breach, it can terminate the agreement–but you can’t get your rights back unless you pay “unreimbursed costs” times three, a fee that the publisher declares “is not intended as a penalty.” From Clause 5.b.:

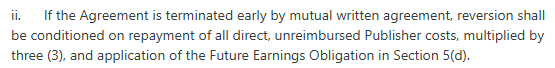

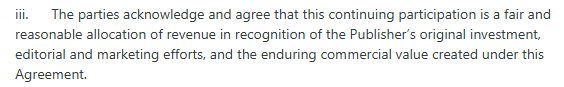

If the contract terminates early by mutual agreement, rather than by breach, you will still owe triple damages:

What’s the Future Earnings Obligation? If rights revert before the end of the contract term, whether because of your breach or a non-breach early termination, and you manage to sell the work elsewhere or self-publish it, you must give Shadow Light 20% of your earnings if publication happens within five years of reversion (or possibly you must pay the 20% for five years–it isn’t really clear). And you have to say thank you.

Other concerns

There are other items I’d flag, including a non-competition clause that extends for the entire term of the contract (which, remember, increases by ten years every time the author turns in a book–non-competition clauses should extend for at most a year or two post-publication); a First Look clause that obliges the author to offer any new work created during the term of the contract to the publisher before offering it anywhere else (a first look clause–also known as a first right of refusal or option clause–should cover only the author’s next non-contracted book in the same genre or for the same market); an Artificial Intelligence clause that requires the author to disclose their use of AI but doesn’t impose any restrictions on the publisher (at a minimum, the publisher should be barred from using or licensing the author’s work for AI training); and a “Limitation of Publisher’s Financial Obligations and Liability” clause that, among other things, relieves the publisher of maintaining “any specific level of financial support” (publishers always maintain that discretion, whether they tell you so or not, but where you see it actually written into a contract, it has the feeling of an advance justification).

But the clauses I’ve unpacked in detail are the main issues, in my opinion.

It’s also interesting to observe how the contract has evolved over time. I’ve seen four Shadow Light Press contracts in addition to the cut-and-paste on Reddit, dating from about a year ago to this past September. While none are author-friendly (they all include the same sweeping claims on rights along with most of the problematic provisions discussed above), there’ve been changes over time to make them even less so.

For example, the oldest contract of the four has a significantly different grant of rights, with the contract term said to “begin upon signing and will conclude 10 years after the Publisher receives the final Work from the author.” Compare that to the most recent grant of rights language, which appears to extend the contract term by 10 years every time the author turns in a book. Also, the clauses dealing with royalties and costs are considerably less detailed, with no mention of “internal costs” and a 50/50 profit split from the start (though they are still paid on net profit, with multiple expense deductions); and the lengthy explainer that prefaces the most recent versions is absent (did the publisher feel the need to anticipate inconvenient questions?).

It all paints a picture of a publisher crafting and changing its contract to tip the scales ever more sharply to its advantage. This tension between the author’s interests and the publisher’s benefit exists in all publishing contracts, of course. Pretty much any publishing contract you’ll ever be offered will favor the publisher. But the best contracts seek to maintain a reasonable balance between these two competing interests–even more so if the publisher is willing to negotiate.

Knowledge is your best defense

As I mentioned at the start of this post, new authors are especially vulnerable to predatory publishing contracts. Inexperience plays a part, as does the difficulty of dense language and legalese–but so does the excitement and validation of a publishing offer, particularly a first-time offer, which can cause writers to forge ahead without fully understanding what they may be committing to, or giving up, by signing that longed-for contract.

Publishers can, and do, take absolute advantage of those things. Where that’s the case, it’s important to call it out. Exposing bad contract language helps writers understand not just what they should avoid, but what they should demand. Whoever made that Reddit post–which I’m guessing took considerable bravery–did a favor to writers everywhere.

Good advice and revealing of the predatory nonsense in the publishing game. Whether it is realized or admitted by most, writers are a vulnerable lot. The desire to have a piece of work you’ve poured many hours into attempting to get to a receptive audience willing to actually pay for your work is daunting. It makes bad deals and outright scams much easier to pull over on a writer. These crooks (yes, I said crooks) use the writer’s desire to be popular, ‘rich’, and rewarded for their efforts as bait to reel you in.

If it looks too good to be true, it is. It is a scam or a legal wrangle to take your efforts and potential income with no responsibility to compensate you. Authors/writers are not the only ones who face these kinds of shady theft in disguise traps; they are simply among the most vulnerable. As your site’s handle points out, writer beware. The desire to see the success of their work has led many self-published authors to make bad decisions. They chase after promotional or get published ideas to promote their work to adnauseium. It has made things a lot harder for budding authors, rendering most to nothing more than mules pulling the cash flow carts in for everyone else in the promotional or publishing game.

At the end of it, your only and best protection is remaining aware and grounded in reality. There are no magic buttons, easy roads, or this one trick solutions to bringing your writing up to a decent-paying income source. Like any other trade or profession, you have to work hard and put some effort into it to succeed, even then, there’s no guarantee you will. The easy way makes you easy.

I would never sign a contract without first consulting an attorney. However, I would never sign a contract that tied me to a publisher for more than 5 years and never one as awful as this nonsense.

That is scary, Victoria. Thanks for the warning. But I find it difficult to understand how anyone could conceive of signing a contract like this.

This has been a wild ride. Thank you.

Excellent article. Thank you, perfect timing.

Omg! Are you kidding me? This is not just predatory language, it’s borderline illegal, theft! I don’t know how could any author sign something like this unless under the influence of heavy postoperative drugs.

It seems like a lot of the authors knew him from the Discord server and he was a “friend.”

That, combined with preying on the newest of new authors who may have been writing their first or second series ever. Said Discord server was a haven for them, with pages and pages of good, actionable advice for the roughly 5,000 members present. But due to the owner of Shadow Light Press’ position as a founding member of the server, the decision was made to completely delete it. It’s currently a really big mess in the web novel scene; drama, lawsuits, authors scrambling to get their IP back.

Great article by the way. Even after spending an hour combing through the contract on Reddit, I still learned some new information.

What a horrifying contract. Goes to show you really need to read and UNDERSTAND what you are signing. I Wouldn’t take that contract at all. Step down with dignity? Only so they can essentially steal your work.

That contract is appalling. It’s worse than a vanity press, it not only takes the author’s money on the back end, but pretty much steals the property. And they can add any kind of marketing or services to the money they’re owed. Thanks for sharing.

Wow! I can’t imagine why any author would sign such a contract. Thanks for your vigilance at keeping us informed.

Wow. Seeing this made me quickly scan the wording with my contract for my last novel with a small press and was happy to see none of that nonsense 🙂 Thank you for bringing this to our attention and I’ll be sure to triple read any contract from here on.

I can see the publisher laughing with glee about adding an additional ten years for every new project submitted (or in some cases, not submitted) and chortling over “Hey, guys, let’s multiply it by three!”

Wow. Pretty horrifying. Thank you as always for sharing, Victoria. I’m also curious if there’s any Termination Clause for authors in this contract?

Only for breach by the publisher.

Thank you, Victoria.